Call of Duty has had celebrity cameos for years, but Black Ops 7 treats its lead like a prestige TV character. Milo Ventimiglia isn’t just a familiar face on the box; he’s the narrative anchor of a sequel that drags Black Ops into 2035, leans into psychological horror, and quietly rewrites what a Call of Duty campaign looks like.

If you know him as Jess from Gilmore Girls, Peter Petrelli from Heroes, or Jack Pearson from This Is Us, Black Ops 7 is the first time you’ll see Ventimiglia fully embedded in a big-budget shooter as the main playable lead, David Mason. The game builds an entire co-op structure, marketing push, and fan conversation around that choice.

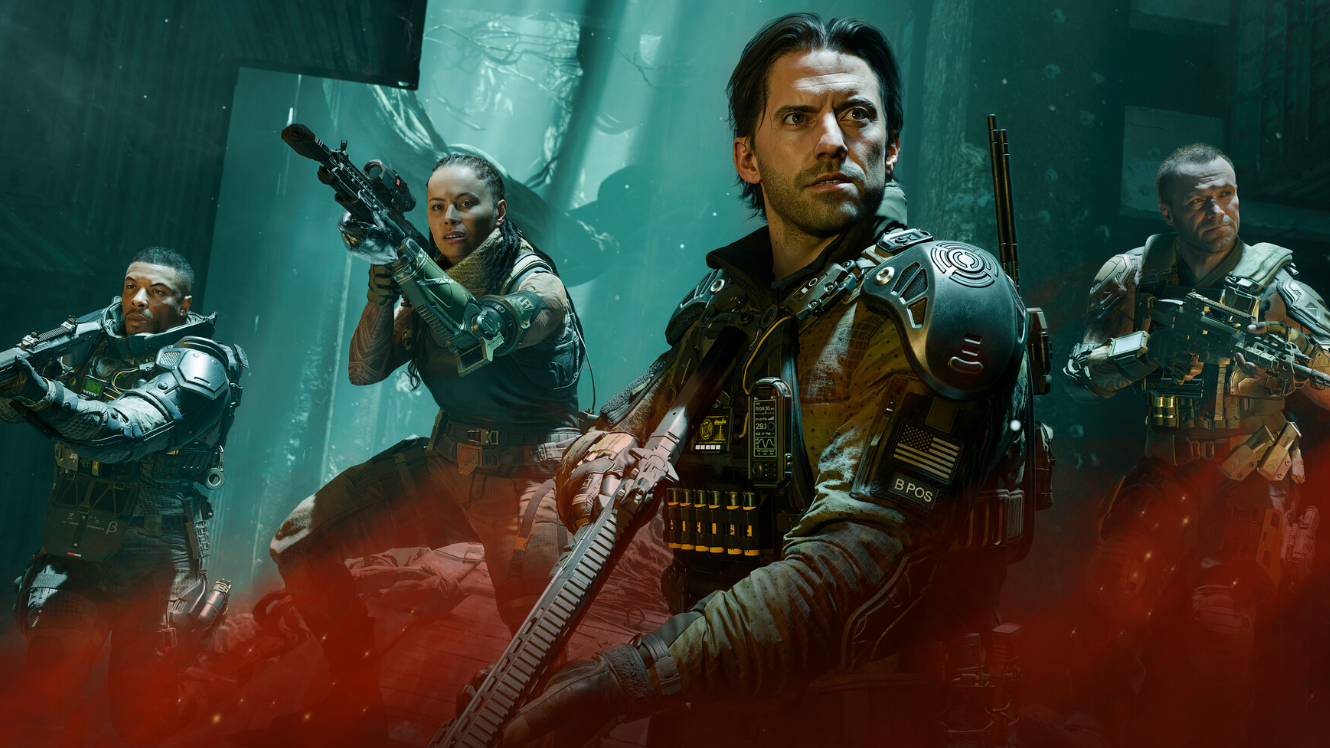

Milo Ventimiglia as David Mason in Black Ops 7

Black Ops 7’s campaign brings back David “Section” Mason, the JSOC commander introduced as a protagonist in Black Ops II. This time, he’s older, fully cyber-augmented, and played in full performance capture by Milo Ventimiglia.

| Character | Actor | Role in Black Ops 7 |

|---|---|---|

| David “Section” Mason | Milo Ventimiglia | JSOC commander, player character, leader of Specter One |

| Emma Kagan | Kiernan Shipka | CEO of The Guild, primary antagonist |

| Mike Harper | Michael Rooker | JSOC Master Chief, returning ally from Black Ops II |

Ventimiglia’s Mason fronts the key art, the trailers, and the in-game squad. He leads the four‑person team “Specter One” through a campaign built around a techno‑corporation called The Guild, a hallucinogenic weaponized toxin, and a fake resurrection of Raul Menendez. It’s a straight continuation of the Black Ops II storyline, but filtered through a very different tone: surreal, conspiratorial, and often closer to Resident Evil than to a traditional war story.

Behind the scenes, Ventimiglia has talked about having to keep the role quiet during production, unable to tell even close contacts that he was attached to a new Call of Duty. That secrecy mirrors the game’s own obsession with deepfakes, black operations, and not knowing what’s real.

How David Mason drives Black Ops 7’s story

The campaign takes place in 2035, roughly a decade after Black Ops II. David Mason now commands Specter One, a JSOC unit operating in and around the Mediterranean megacity of Avalon. The team is pulled back into the Menendez myth when a video circulates showing the long‑dead terrorist threatening to destroy the world in three days.

That premise pulls Mason into a layered mystery built on three pillars:

| Story pillar | What it means for Mason |

|---|---|

| Cradle toxin | Mason is repeatedly exposed to a hallucinogenic chemical that weaponizes fear and trauma, forcing him to relive past events. |

| The Guild | He faces a “legitimate” tech conglomerate that evolved from a criminal group, fronted by Emma Kagan as a new kind of villain. |

| Menendez’s legacy | Instead of fighting Menendez himself, Mason has to deal with deepfakes and the political power of his image. |

Because Cradle amplifies whatever is in Mason’s head, his personality and history directly shape the playable hallucinations. Players revisit Nicaragua, Angola, and other key historical beats as distorted nightmare spaces. Mason confronts visions of Menendez, his father Alex, and even Frank Woods rewritten by his own guilt.

Those sequences would not land without a convincing lead performance. Ventimiglia’s Mason swings from controlled commander to panicked son in seconds, and the game leans on that range. In quiet dialogue scenes, he’s the weary operator who has seen too much. In Cradle‑induced hallucinations, he’s visibly unsure whether anything he’s seeing is real.

What Milo Ventimiglia brings to Mason compared to earlier Black Ops

Previous Black Ops campaigns featured strong performances, but the structure often hopped between multiple protagonists and timelines. Black Ops 7 still spreads screen time across the full Specter One squad, yet it ties every major hallucination, memory, and moral choice back to Mason’s point of view.

That focus lets Ventimiglia shape the character in ways that feel closer to long‑running TV arcs than one‑off shooter cameos:

- Continuity of trauma: Mason’s unresolved issues with his father and Menendez are no longer just lore; they are entire mission spaces you fight through while he processes them.

- Shared hallucinations: The rest of Specter One literally sees Mason’s memories when Cradle hits, giving his inner life consequences for the whole team.

- Command presence: In co-op play, Mason has to function as both an avatar and a leader whose orders players hear over voice chat-style barks.

There’s also a tonal contrast that plays to Ventimiglia’s strengths. Mason is written as a competent, decisive operator, but the campaign constantly undercuts that certainty with unreliable realities. You can feel the friction between the “Black Ops hero” archetype and a guy who doesn’t know if his senses are lying to him.

That tension gives Black Ops 7 room to ask questions that fit the series’ obsession with paranoia: Who controls the narrative when deepfakes can resurrect a terrorist? What does justice look like when a corporation like The Guild can weaponize fear at scale? Mason, as played by Ventimiglia, is the lens through which those questions land.

Inside Specter One: Mason’s squad and relationships

Milo Ventimiglia doesn’t carry the story alone. Specter One is built as a four‑person ensemble, with Mason at the center:

| Squad member | Performer | Dynamic with Mason |

|---|---|---|

| Mike Harper | Michael Rooker | Old friend and fellow SEAL, grounding Mason with shared history from Black Ops II. |

| Eric Samuels | John Eric Bentley | Analyst‑type operator, often the quiet counterpoint to Mason’s more emotional reactions. |

| Leilani “50/50” Tupuola | Frankie Adams | Cyborg soldier whose body is literally shaped by The Guild’s tech, highlighting what Mason is fighting against. |

The script doesn’t give each character unique gameplay powers, but the performances still matter. Harper’s dialogue reminds Mason of who he was before cybernetics and Cradle. Tupuola embodies what happens when human beings are treated as platforms for technology. Samuels is the one most likely to question what they’re seeing.

Because the campaign is designed for up to four players in co‑op, the banter and callouts have to work whether you’re hearing them between friends on headsets or listening solo with AI slots left empty. That makes Mason’s lines do double duty as both storytelling and a subtle tutorial, and Ventimiglia’s delivery stays measured enough that repeated barks don’t grate.

Emma Kagan vs. David Mason: a different kind of Black Ops villain

Black Ops villains have usually been warlords, rogue agents, or ideologues. In 7, the main antagonist is something more contemporary: Emma Kagan, the CEO of The Guild, played by Kiernan Shipka.

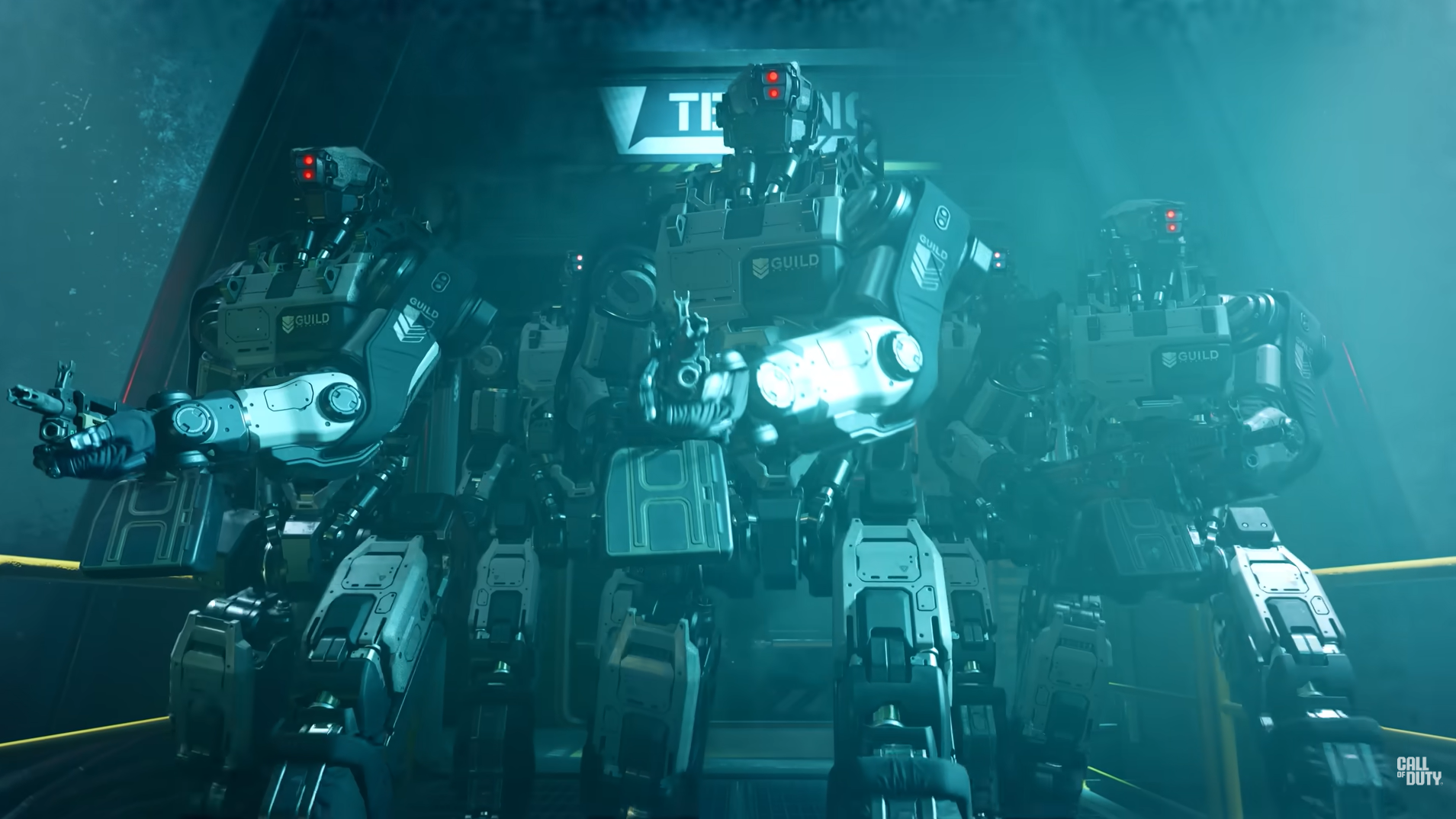

The Guild presents itself as a technology and security company, but operates like a privatized state. It controls Avalon, fields its own private army, and uses Cradle to manufacture chaos it can then “solve.” Ventimiglia’s Mason spends the campaign trying to disentangle the fake Menendez threat from Kagan’s actual plan to profit from global fear.

That dynamic puts Mason opposite someone who fights with narrative, data, and biotech instead of nukes. Kagan’s weapon isn’t just Cradle; it’s the ability to convince the world that Menendez is back, or that The Guild is the only path back to stability. Mason is forced into a role beyond soldier: he has to become a witness against her, capturing proof rather than killing an obvious bad guy on a battlefield.

When Mason finally confronts Kagan, the game leans heavily on both performances. She remains calm, almost amused, in the face of capture. He’s visibly exhausted, trying to hold onto a sense that any of this will matter once the public sees the truth.

Why the always-online campaign matters for a performance-led story

Black Ops 7’s campaign is controversial for structural reasons. It is:

- Always online, even when you play solo

- Built around four‑player co-op with no AI squadmates filling empty slots

- Lacking traditional checkpoints and mid‑mission pause

- Willing to boot inactive players from sessions after some idle time

Those choices tie directly into how Mason is experienced. Because missions are tuned for a full squad in a connected world, Ventimiglia’s performance has to withstand repeated replays when sessions fail or players drop. When you get disconnected and have to restart, you’re replaying not only combat beats but also cutscenes and in‑mission dialogue anchored on Mason.

The “Endgame” activity reinforces this. Once the 11‑mission story is complete, a persistent mode opens up across Avalon for up to 32 players. It uses the same abilities, weapon unlocks, and character builds you developed in the campaign, but recontextualized as an extraction shooter. Mason and company become ongoing avatars in a shared space rather than one‑and‑done protagonists.

For an actor, that means playing a character who has to work as both the center of a fixed narrative and the face of a repeatable live‑service loop. It’s closer to voicing a long‑running seasonal character than a static campaign hero.

How Black Ops 7 reframes Call of Duty’s identity around its cast

Black Ops 7 lands in a tougher landscape than earlier entries. Battlefield 6 has reclaimed attention on the “serious war” side of the genre. Some longtime Call of Duty players are frustrated with crossover skins and live‑service bloat that blurred the series into Fortnite‑like chaos. Game Pass price changes have made the economics of annual shooters more visible.

In that context, the decision to front the game with Milo Ventimiglia and Kiernan Shipka is not just about stunt casting. It signals a shift back toward a more defined identity: clandestine operations, paranoia about truth and perception, and an ensemble cast that feels more like a conspiracy thriller than a military sim.

Ventimiglia himself has pointed to that storytelling focus, describing this campaign as going further than earlier entries in emotional scope and cinematic ambition. From the way missions twist reality around Mason’s trauma to the decision to ground everything in one city contaminated by one toxin, Black Ops 7 is built to support that kind of lead.

If you come to the series for its competitive multiplayer or Zombies modes, Mason may still be just the guy on the box. But if you care about where Black Ops goes as a story, Milo Ventimiglia’s take on David Mason is now the template: a returning protagonist carrying years of history into a future defined less by hardware and more by the stories people choose to believe.